How AI-Generated Books Could Hurt Self-Publishing Authors

Self-publishing authors may end up as collateral damage in the rising tide of AI-generated books appearing at major online retailers.

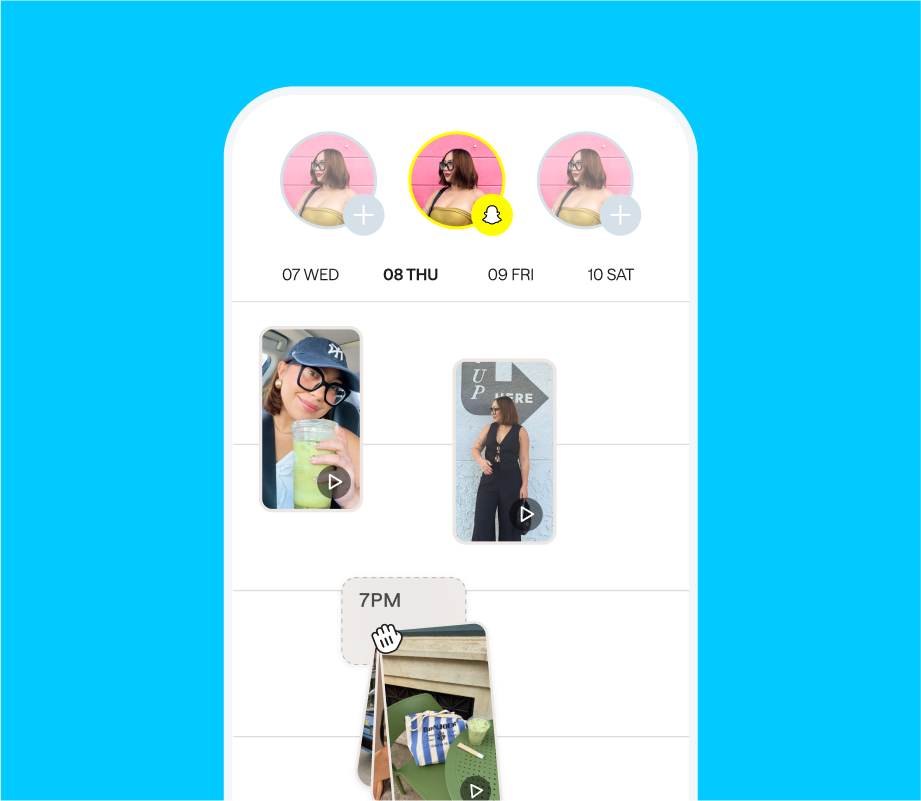

Update (Jan. 24, 2025): Retailers and distributors like Barnes & Noble and IngramSpark have been creating stricter policies to keep out low-quality content that’s increasingly AI generated. Similarly, distributor Draft2Digital (used by self-publishing authors) has also had to keep an eye on the increased level of publishing activity on its platform. In 2024, the volume of material coming into the D2D platform has was trending at roughly 50 percent more than usual. Fortunately, COO of Draft2Digital, Dan Wood, says it’s easy to track the bad actors because “normal authors don’t release 10 books in a day.” D2D looks at account statistics and other account data to help them identify players they might prefer not to host or enable. In the past, these sorts of players would use ghostwriters in developing countries or other cheap methods of generating material, but it’s now obviously AI. “We’ve always had a policy against low-quality works,” he says. “We think it’s in our best interest to send books to the retailers that the readers are going to actually want.” Generally, D2D shuts down the bad actors before the books even make it to the retailers. In some cases, if something slips past their monitoring, they will simply take all material down upon discovery.

In 2024, as part of a quality-control initiative, Barnes & Noble began limiting the number of print titles they offer in their online store, and they de-listed thousands of self-published titles without warning across all formats. Categories affected include erotica, public domain works, and summary titles (which are often low-quality).

Amazon has also put on some guardrails for KDP: only 3 new published titles per day are allowed and identity authentication is now required. They’ve also started limiting or prohibiting certain types of low-quality titles. Amazon’s KDP guidelines now state, “Companion guides (including summaries, study guides, workbooks, analyses, and other related content based on other books) are not allowed, with limited exceptions for guides with positive reader engagement.”

Ebook distributor OverDrive also limits summary titles in its online catalogs. This amounts to 30,000 titles in the case of OverDrive. The reason given for removal? No one likes them.

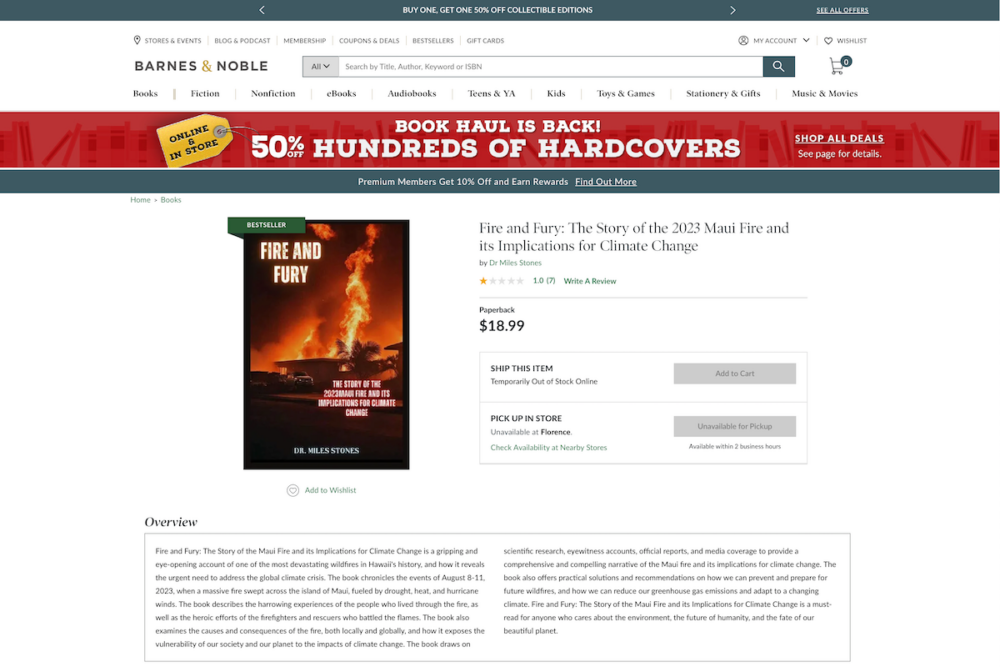

Just two days after the Maui wildfires began, on Aug. 10, a new book was self-published, Fire and Fury: The Story of the 2023 Maui Fire and its Implications for Climate Change by “Dr. Miles Stones” (no such person seems to exist). I learned about the book from this Forbes article, but by then, Amazon had removed the book from sale. Amazon had no comment for Forbes on the situation.

Curious about how far the book might have spread, I did a Google search for the book’s ISBN number (9798856899343). To my surprise, I saw the book was also for sale at Bookshop and Barnes & Noble. I tweeted about the situation, noting that IngramSpark, a division of Ingram, must be distributing these books to the broader retail market. My assumption was that retailers, in particular Bookshop, would not accept self-published books coming out of Amazon’s KDP. (Amazon KDP authors can choose to enable Amazon’s Expanded Distribution at no cost, to reach retail markets outside of Amazon.)

It turns out my assumption was wrong. Bookshop does accept self-published books distributed by Amazon, and here things get a little convoluted. Amazon Expanded Distribution uses Ingram to distribute; Ingram is the biggest book distributor and there isn’t really any other service to use for distribution as far as the US/UK.

However, Bookshop’s policy is not to sell AI-generated books unless they are clearly labeled as such, so Fire and Fury was removed from sale after they were alerted to its presence. Bookshop’s founder Andy Hunter tweeted: “We will pull them from @Bookshop_Org when we find them, but it’s always going to be a challenge to support self-published authors while trying to NOT support AI fakes.”

And now we come to why self-publishing authors have reason to be seriously concerned about the rising tide of AI-generated books.

- Amazon KDP is unlikely to ever prohibit AI-generated content. Even if it did create such a policy, there are no surefire detection methods for AI-generated material today.

- Amazon KDP authors can easily enable expanded distribution to the broader retail market at no cost to them. It’s basically a checkbox.

- Amazon uses Ingram to distribute, and Ingram reaches everyone who matters—bookstores, libraries, and all kinds of retailers. Ingram does have a policy, however, that they may not accept “books created using artificial intelligence or automated processes.”

- Based on what happened with Fire and Fury, Amazon’s expanded distribution can make a book available for sale at Barnes & Noble and Bookshop in a matter of days.

If the rising tide of AI-generated material keeps producing such questionable books—along with embarrassing and unwanted publicity—one has to ask if Barnes & Noble and Bookshop might decide to stop accepting self-published books altogether from Ingram or otherwise limit their acceptance. Obviously not good news for self-published authors, or Ingram either.

What are some potential remedies?

- Ingram is an important waypoint here. They’ve put stronger quality control measures in place before. Perhaps they can be strengthened to prevent the worst material from reaching the market outside of Amazon.

- Amazon’s Expanded Distribution requires use of ISBNs; if authors don’t purchase their own ISBNs, they can take Amazon-provided ISBNs. Would it be possible for retailers to block any title with an Amazon ISBN? (ISBNs identify the publisher or where the material originated from.) Or any book distributed via Amazon? While that may be unfair to honest people who prefer to use Amazon’s Expanded Distribution, such authors/publishers would still have the option of setting up their own IngramSpark account. IngramSpark has no upfront fees and also provides free ISBNs.

- Maybe IngramSpark or other retailers put a delay on making Amazon’s Expanded Distribution titles available for sale. Amazon already states it can take up to eight weeks for the book to go on sale. So why not make such titles wait?

Free ISBNs from Amazon unfortunately contribute to this problem

ISBNs are a basic requirement to sell a print book through retail channels today. In the US, it is expensive to purchase ISBNs—it’s nearly $300 for ten. Amazon KDP does not require authors to purchase ISBNs and will give you ISBNs for free all day if you need them. Over time, others like IngramSpark and Draft2Digital have also made ISBNs free to make it easier for self-publishing authors to distribute their work.

While it’s admirable to lower the barriers for authors who have limited funds, free ISBNs are supercharging the distribution of AI-generated materials to the wider retail market. An immediate way to stem this tide of garbage in the US market? Stop giving out free ISBNs. Make authors purchase their own. (Lest I be misunderstood, by “garbage” I mean books that are questionable in the extreme, like the Maui book mentioned above, or shoddy travel books that The New York Times reported on, or other materials readers would not buy if they understood what it was.)

There’s a huge advantage to making authors obtain or purchase their own ISBNs: it creates an identifiable publisher of record. The publisher of record would be listed at retailers. Currently, fraudsters using Amazon KDP are able to hide behind Amazon-owned ISBNs; their books are simply listed as “independently published.” It would be marvelous to take away that fig leaf. Sure, fraudsters could create sham entities that mean nothing and are unfindable in the end, but at least you could connect the dots on all the titles they’re releasing—plus Bowker (the ISBN-issuing agency in the US) would see who’s doing the purchasing and possibly put their own guardrails in place. My hope is these entities would choose not to buy ISBNs at all and this activity would become limited to the backwaters of Amazon.

[Added Aug. 21] In countries where ISBNs are free for authors, my assumption is that one can tie an ISBN back to a real person or publishing company. If anyone can confirm or deny how it works outside the US for free ISBNs, I’d appreciate your comment on this point.

Professional self-publishing authors who distribute widely outside of Amazon are buying their own ISBNs already. Those who aren’t? I would consider it, because if nothing changes about the current situation, we may be entering a period where a book without an identifiable publisher (or author) is immediately considered suspect. And that’s another problem for self-publishing authors.

.jpg)

![How Marketers Are Using AI for Writing [Survey]](https://www.growandconvert.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ai-for-writing-1024x682.jpg)

![311 Instagram caption ideas [plus free caption generator]](https://blog.hootsuite.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/instagram-captions-drive-engagement.png)

![Here’s Why Integrated Marketing Is So Effective [+ Best Practices]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/Untitled%20design%20%2830%29%20%281%29.jpg)