An Argument for Why The Christmas Carol Is Really a Coming-of-Age Story

One writer asserts that Scrooge’s arc isn't that of becoming a new person, but confronting his core wound and rediscovering his true self.

Today’s post is by author, filmmaker, and coach Colleen Patrick.

True or false: Ebenezer Scrooge changes who he is at the end of Charles Dickens’ immortal classic, A Christmas Carol.

When I begin my writing seminars with this challenge, a wave of hands flies up when I ask, “True?”

The eager group becomes self-righteously still, arms crossed, for, “False?”

When I proclaim the premise false, a disbelieving cacophony ensues. “That’s crazy!” “Of course he changed!” “No way!” “He completely transformed!”

Before desks can be overturned, notebooks thrown, pencils broken, and the otherwise docile writers trip over one other, desperate to escape and demand a refund, I explain.

My belief is that Scrooge became who he really is—or was, inside, all along. But he was too terrified to face his past because of the emotional wounds and turmoil he was dealt in childhood.

Dickens’ Christmas treatise is the gold standard for understanding human psychology, far ahead of its time. As serious as the subject is, he chose to tell his story using a whimsical writing style, no doubt to lower our resistance to deal with these serious, mysterious ordeals.

Before I deconstruct Ebenezer’s literary journey to prove my case, let’s gain some insights about the preeminent authority of A Christmas Carol: Charles Dickens.

In autumn 1843, Dickens’ funds were depleted, his career careening with poor sales of his latest episodic, The Life and Times of Martin Chuzzlewit. Desperate to excite readers again and please his bankers, he decided to write a full book with a Christmas theme. He had just begun dabbling with the world of spirits and poltergeists, so he began writing the ghostly A Christmas Carol October 14, 1843. It was released just two months later, on December 19. He wrote it so quickly he was not entirely happy with the published work—which, in only a matter of days, became the bestselling book in all of 1843.

In fact, the book’s phenomenal popularity, as well as its many iterations, continues nearly 200 years after its initial release.

I contend its audience magnetism derives from Dickens’ character structure for Scrooge. After dramatizing how the world sees Ebenezer, and how he experiences the world, Dickens takes us more deeply into the mind and heart of Scrooge than we’d normally be allowed any male character at that time.

It’s an inside job. Everything and everyone he grapples with emanates from his mind, his gut, his heart, his imagination. The ghost of Marley and the Spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Future appear from his inner tumult, feelings he has been fighting to mute for so many years. His dilemmas become like a large balloon he strives to hold underwater—which, as we all know, is impossible. He tries to dismiss them, because, after all, they just might be conjured from “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato.”

No. They’re created from his inner upheaval, facing his woulda, coulda, shoulda life. Reflection is not Ebenezer’s strong point. He reluctantly scuffles, parries and thrusts with Marley, the Christmas Spirits and every bombshell revelation he encounters on his journey of self-discovery, each one creating more conflict and epiphanies to pull the story forward.

The inciting incident is not Bob Cratchit’s sad Tiny Tim story or Marley’s terrifying apparition or a pair of do-gooder business peers seeking donations for the poor. It’s his full of Christmas cheer adult nephew, Fred, who intrudes at Scrooge’s place of business, disgusting the “Bah! Humbug!” miser.

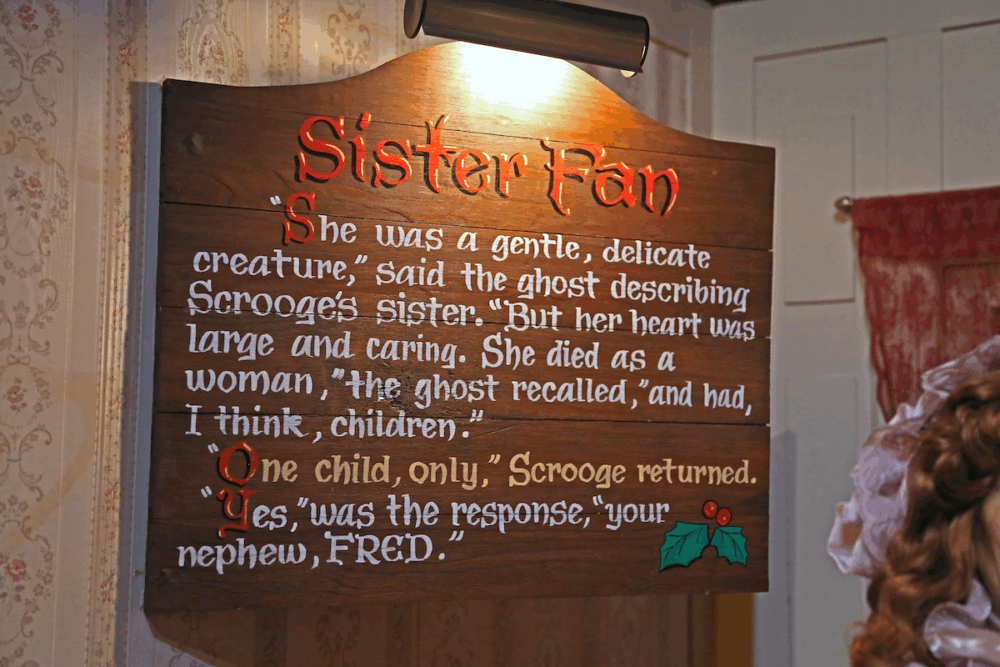

Scrooge ridicules Fred’s ebullient Christmas demeanor and dismisses him, burying the pain he carries from seeing his nephew under any circumstance. The reason: Scrooge blames his nephew for the death of the only person who ever loved Ebenezer unconditionally—his sister, Fan. She died giving birth to Fred. Incidentally, Dickens had a sister named Fan.

We get to know characters by the way they react to whatever or whoever confronts them. Our attention remains rapt when we discover how characters respond: what they’re feeling, what they’re thinking. Being literary sleuths, we want to solve this mystery—what makes Scrooge behave so badly? How can he be redeemed?

Dickens uses conversation—inner monologues from Scrooge and dialogue with interlopers—to show us what he’s thinking, remembering, and feeling. Each new character forces him to react—to deal with feelings and memories he believed long sealed away.

Compliments of the Ghost of Christmas Past, Scrooge sees the school and pals that made him so happy, he can’t help but clap his hands and laugh. Then he sees himself—broken-hearted, though putting on a brave face for his peers, left to suffer Christmas alone in his room as they happily leave to enjoy the holidays with their families. Scrooge weeps openly, recalling the pain he locked in.

This is followed by the joy of his younger sister, Fan, surprising him. She has arranged to take him home for Christmas. She reaches up to hug her taller brother, proclaiming their father is so much kinder and happier now. Scrooge is overwhelmed with gratitude. Fan’s loving, generous, kind older brother was rewarded with her appreciation, affection and protection; he’s thrilled.

CUT TO: Fan, the adult, giving birth to Fred, her last words beseeching Scrooge to watch over her baby. Scrooge again weeps openly as he witnesses the only person who ever loved him unconditionally slipping away from her life. And his. Because of that baby. Fred.

I maintain that without these early scenes, we would never believe in Scrooge’s redemption on Christmas day. This is who the guy really is. But, like many who experience a severe trauma, he becomes emotionally stuck. He locks out the possibility of love because even the thought of its loss is too excruciating to bear.

Without proper guidance or therapy, kids who are raised in out-of-control environments tend to be controlling adults. Scrooge found what he could control—business and money. Money that never bought him happiness, but power and control are always for sale.

Later, despite a lovely young woman who wanted to marry him, Scrooge prioritized peer approval, privilege, and profit. He recalls his first boss, Mr. Fezziwig, who threw wonderful Christmas parties and gave generous bonuses. He relives being disrespectful to Mr. Fezziwig, which, in hindsight, he regrets. A mature breakthrough: expressed empathy. Now Scrooge is open to receiving new life information about what he’s previously missed because of his emotional blinders.

Thanks to the Ghost of Christmas Present, Scrooge becomes swept up in the heady bliss of the season he celebrated years ago, passing by new toys in shop windows, then experiencing the joy of an invisible visit to the poor, but loving, Cratchit family. While Bob Cratchit did not disparage his boss at their meager Christmas goose dinner, his wife does—loudly, sparing no insults.

Scrooge’s empathy expands once more to wonder after the sickly Tiny Tim. The Ghost grimly informs Scrooge that without proper care, the diminutive child who walks with a crutch will die. Scrooge is stricken. Concerned. For the first time we see him care about something—someone—more deeply than business, money or being on the lookout for someone looking to cheat him.

The Ghost of Christmas Future shows Scrooge that when he dies, he will reap what he has sown. Those left behind are near celebratory—ridiculing his death, stealing his burial clothes and jewelry, they would have taken his teeth if they had access.

But unlike before his nocturnal Spirits’ reckoning, his attention remains on the Cratchits and sickly Tiny Tim, and his unkept vow to his dear Fan—to watch over Fred.

Arising Christmas morning, he is on fire with the Spirit of Christmas. He has a life to live! To give! Everything good he felt as a boy is now alive and energized in his aging body—whose spine is again straightened, not curved and bent over like an old man. What thrilled him at Christmas as a boy has come full circle. It’s once again alive in him now as an adult.

Radiating the ebullience of the season, he sets out to make amends to his nephew, bring gifts and a turkey to the Cratchits so they might all share a genuinely Merry Christmas, complete with a pay raise for Bob and a position for his older son.

Scrooge chose to live in gratitude rather than anger at what he doesn’t have or what he believed was taken from him. Thus, the elder Ebenezer Scrooge becomes the person he had locked inside most of his life, maturing with every revelation along the way. A true coming-of-age story.

Because Dickens took us on this journey, first showing us the outside world of Scrooge, how others react to him negatively, then taking us through the inner sanctum of Scrooge’s mind, we are hooked, possibly discovering the Scrooge inside us, wishing we could also find a similar redemption. I mean, after all, if Ebenezer Scrooge can do it…

I’d be remiss not to mention Dickens’ focus on life and death. Or rather, early on, Scrooge’s fear of death, and later, living a full life, having no fear of death.

The book starts out by declaring Marley is as dead as a door nail. Buried. Gone. Just like Ebenezer’s feelings and wounded memories. When Marley appears as an apparition, Scrooge is terrified. Of death. Of the ghost’s message. Near the end, he’s fearful of his own passing. But when he reclaims the youthful bliss of living out loud, giving, sharing, loving, then joining his nephew (his birth family (and then the Cratchits (his chosen family), his fear of death vanishes.

In one night’s drama, Dickens has brought us through a personal evolution many of us have spent years in therapy, self-help books and “personal growth” seminars trying to achieve.

I declare to my students: No matter how old the body, it’s never too late! Scrooge’s is a coming-of-age story.

![The 11 Best Landing Page Builder Software Tools [2025]](https://www.growthmarketingpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/best-landing-page-software-hero-image-1024x618.png?#)

![What Is Generative Engine Optimization [Tips & Workflows To Do It]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/What-Is-Generative-Engine-Optimization-Tips-Workflows-To-Do-It-1.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1745607929&s=6f75f1f02c531af0f80acb12517c8bab#)

![Social media image sizes for all networks [May 2025]](https://blog.hootsuite.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Social-Media-Image-Sizes-2023.png)

![The fastest growing social media platforms of 2025 [new data]](https://53.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/53/fastest-growing-social-media-platforms.jpg)