WE NOW BELONG TO OURSELVES

Activist and historian Edmonds began to research the life of her great-great-grandfather, Jefferson Lewis Edmonds, in 2009, inspired by her father to “care for our archive, the value of it.” Like much else in Black history, that archive was scattered and incomplete: Edmonds hit the documentary trail at home in Los Angeles but traveled to Ghana to fill in missing pieces of the story. “I didn’t have an end plan. All I knew was that I had to go,” she writes. Jefferson, as she calls him, was less concerned with the ancestral homeland: As he wrote in 1910 in the newspaper he founded, The Liberator, “It has been fully 200 years since our ancestors left Africa, so we have lost track of whatever right or title to any property they may have held.” Instead, Jefferson maintained, African Americans were truly Americans, deserving of the full citizenship rights that had been frustrated by the failure of Reconstruction. In that light, Jefferson, born in slavery in the Deep South, counseled that Black Americans would do well to abandon the region and make, in his instance, for Los Angeles, where The Liberator would come to enjoy a subscriber base of nearly half the city’s African American population: Jefferson believed strongly that the community needed not just jobs and homes, but also “a record of their lives.” He strongly advocated for land ownership and entrepreneurship, no easy task even in California, which had Jim Crow laws of its own. Edmonds’ narrative is conversational in tone and sometimes wanders, but it makes an important point that the stories that each Black American family has gathered need “a home and an advocate,” and ideally a font for many more such books.

Activist and historian Edmonds began to research the life of her great-great-grandfather, Jefferson Lewis Edmonds, in 2009, inspired by her father to “care for our archive, the value of it.” Like much else in Black history, that archive was scattered and incomplete: Edmonds hit the documentary trail at home in Los Angeles but traveled to Ghana to fill in missing pieces of the story. “I didn’t have an end plan. All I knew was that I had to go,” she writes. Jefferson, as she calls him, was less concerned with the ancestral homeland: As he wrote in 1910 in the newspaper he founded, The Liberator, “It has been fully 200 years since our ancestors left Africa, so we have lost track of whatever right or title to any property they may have held.” Instead, Jefferson maintained, African Americans were truly Americans, deserving of the full citizenship rights that had been frustrated by the failure of Reconstruction. In that light, Jefferson, born in slavery in the Deep South, counseled that Black Americans would do well to abandon the region and make, in his instance, for Los Angeles, where The Liberator would come to enjoy a subscriber base of nearly half the city’s African American population: Jefferson believed strongly that the community needed not just jobs and homes, but also “a record of their lives.” He strongly advocated for land ownership and entrepreneurship, no easy task even in California, which had Jim Crow laws of its own. Edmonds’ narrative is conversational in tone and sometimes wanders, but it makes an important point that the stories that each Black American family has gathered need “a home and an advocate,” and ideally a font for many more such books.

![How To Drive More Conversions With Fewer Clicks [MozCon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_RebeccaJackson_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1750097440&s=282171eb79ac511caa72821d69580a6e#)

![Brand and SEO Sitting on a Tree: K-I-S-S-I-N-G [Mozcon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_LidiaInfante_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1749465874&s=56275e60eb1f4363767c42d318c4ef4a#)

![The 11 Best Landing Page Builder Software Tools [2025]](https://www.growthmarketingpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/best-landing-page-software-hero-image-1024x618.png?#)

![How to Create an SEO Forecast [Free Template Included] — Whiteboard Friday](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/WBF-SEOForecasting-Blog_Header.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1694010279&s=318ed1d453ed4f230e8e4b50ecee5417#)

![How To Build AI Tools To Automate Your SEO Workflows [MozCon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_Andrew_London-1.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1749642474&s=7897686f91f4e22a1f5191ea07414026#)

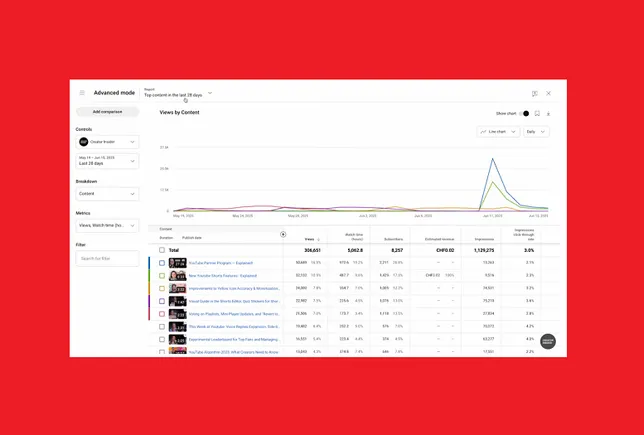

![How Social Platforms Measure Video Views [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/AncxHXS242CT-kDlEkGZi7uQ2k70-ebTAh7Lm14QKb8/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9ob3dfcGxhdGZvcm1zX21lYXN1cmVfdmlld3MucG5n.webp)

![Brand pitch guide for creators [deck and email templates]](https://blog.hootsuite.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/brand-pitch-template.png)

![AI marketing campaigns only a bot could launch & which tools pitch the best ones [product test]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/ai-marketing-campaigns.webp)