THE TALE OF MR. CROCODILE TAKES TEA

The author returns to the world of anthropomorphic animals, this time in a transcontinental adventure that explores what it means to be human—even for members of other species. The story opens in an unnamed African village on the banks of the Sillibilli River, where a family of crocodiles, led by the very large Mr. Crocodile, sits down to an elegant high tea with human village leaders and an astonished “Great White Hunter.” A flashback explains how Kita, a villager, persuaded Mr. Crocodile, formerly known as Sandbank, that he was “a Person” and therefore it’s inappropriate for him to pull other people into the river, even for fun. The high-tea tradition grows out of Mr. Crocodile’s new understanding of his personhood, and when he learns that the hunter, Henry Henderson, has been targeting crocodiles elsewhere, he insists on inviting him to tea to establish their common personhood. Mr. Crocodile informs the astonished hunter that, because he’s had dreams of a friendly English boy named Thomas, he and a group of crocodiles plan to travel to England. Mr. Crocodile and his companions soon arrive in London’s Crouch End area, where they meet Thomas and quickly charm his neighbors. However, it becomes clear that Henderson plans to abuse and exploit the crocodiles during their stay. Mr. Crocodile’s resentment grows, but when he runs into a gnu, he interrogates his own assumptions about who counts as a person. He has an epiphany, and soon organizes a multispecies event to demonstrate the concept of equality.Lee presents a story that’s highly readable and often charming, and its didacticism doesn’t overwhelm the story. The text’s frequent, idiosyncratic use of capital letters (“I will give you as fine an English High Tea as I can manage which we will enjoy together as fellow Persons,” says Mr. Crocodile at one point) adds a flavor of antiquity to the prose, which also effectively contributes to its arch tone. It’s also enhanced by the fact that the book is not at all subtle in its messaging, as when Mr. Crocodile criticizes an atlas that refers to a river as “crocodile infested” and asks Thomas if it would be fair to call Crouch End “INFESTED BY HUMAN PERSONS,” which the boy agrees is indeed inappropriate. However, the book’s subtitle, which refers to the story as a fable, adequately prepares readers for its message-driven approach. Mr. Crocodile’s big reveal will remind readers that it was the African villagers, not Henderson, who taught him about personhood. That said, the book does not fully grapple with Europe’s relationship with Africa. Also, Mr. Crocodile’s enthusiasm for tea and wearing top hats—as depicted in Hunkeler’s realistic, painterly full-color illustrations, which depict major events throughout—may remind readers of Jean de Brunhoff’s stories of Babar the Elephant and their colonialist overtones. Still, it’s a cohesive story that generally overcomes such flaws.

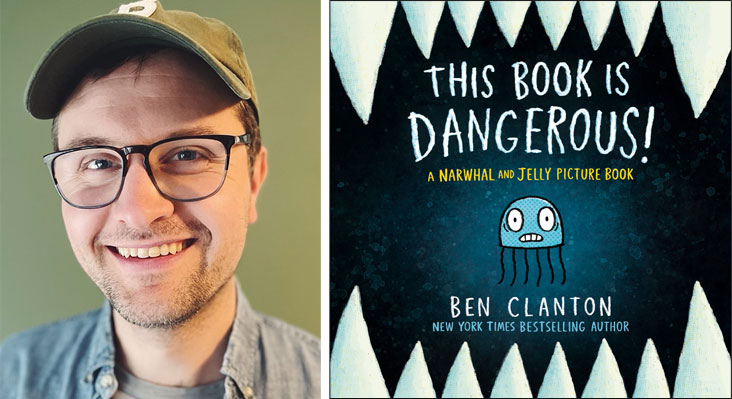

The author returns to the world of anthropomorphic animals, this time in a transcontinental adventure that explores what it means to be human—even for members of other species. The story opens in an unnamed African village on the banks of the Sillibilli River, where a family of crocodiles, led by the very large Mr. Crocodile, sits down to an elegant high tea with human village leaders and an astonished “Great White Hunter.” A flashback explains how Kita, a villager, persuaded Mr. Crocodile, formerly known as Sandbank, that he was “a Person” and therefore it’s inappropriate for him to pull other people into the river, even for fun. The high-tea tradition grows out of Mr. Crocodile’s new understanding of his personhood, and when he learns that the hunter, Henry Henderson, has been targeting crocodiles elsewhere, he insists on inviting him to tea to establish their common personhood. Mr. Crocodile informs the astonished hunter that, because he’s had dreams of a friendly English boy named Thomas, he and a group of crocodiles plan to travel to England. Mr. Crocodile and his companions soon arrive in London’s Crouch End area, where they meet Thomas and quickly charm his neighbors. However, it becomes clear that Henderson plans to abuse and exploit the crocodiles during their stay. Mr. Crocodile’s resentment grows, but when he runs into a gnu, he interrogates his own assumptions about who counts as a person. He has an epiphany, and soon organizes a multispecies event to demonstrate the concept of equality.

Lee presents a story that’s highly readable and often charming, and its didacticism doesn’t overwhelm the story. The text’s frequent, idiosyncratic use of capital letters (“I will give you as fine an English High Tea as I can manage which we will enjoy together as fellow Persons,” says Mr. Crocodile at one point) adds a flavor of antiquity to the prose, which also effectively contributes to its arch tone. It’s also enhanced by the fact that the book is not at all subtle in its messaging, as when Mr. Crocodile criticizes an atlas that refers to a river as “crocodile infested” and asks Thomas if it would be fair to call Crouch End “INFESTED BY HUMAN PERSONS,” which the boy agrees is indeed inappropriate. However, the book’s subtitle, which refers to the story as a fable, adequately prepares readers for its message-driven approach. Mr. Crocodile’s big reveal will remind readers that it was the African villagers, not Henderson, who taught him about personhood. That said, the book does not fully grapple with Europe’s relationship with Africa. Also, Mr. Crocodile’s enthusiasm for tea and wearing top hats—as depicted in Hunkeler’s realistic, painterly full-color illustrations, which depict major events throughout—may remind readers of Jean de Brunhoff’s stories of Babar the Elephant and their colonialist overtones. Still, it’s a cohesive story that generally overcomes such flaws.

![How To Launch, Grow, and Scale a Community That Supports Your Brand [MozCon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_Areej-abuali_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1747732165&s=beb7825c980a8c74f9a756ec91c8d68b#)

![Clicks Don’t Pay the Bills: Use This Audit Framework To Prove Content Revenue [Mozcon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_Hellen_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1747758249&s=9f3c5b1b7421f862beace1cb513053bb#)

![How To Create an Integrated Strategy That Increases Brand Mentions and Visibility [Mozcon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_JamesH_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1747780409&s=9bf9f0a2623b4a8be6eaf8f235115505#)

.png)

![The 11 Best Landing Page Builder Software Tools [2025]](https://www.growthmarketingpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/best-landing-page-software-hero-image-1024x618.png?#)

![Social media image sizes for all networks [June 2025]](https://blog.hootsuite.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Social-Media-Image-Sizes-2023.png)

![What you're doing wrong in your marketing emails [according to an email expert]](https://53.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/53/jay-schwedelson-mim-blog.webp)

![These AI workflows can 10X your marketing productivity [+ video]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/Untitled%20design%20-%202025-05-29T135332.005.png)