The Secret to Avoiding a Sagging Memoir Middle

The finest memoirs are distilled experiences: the more you compress, the more potent your story becomes.

Today’s guest post is by writer and coach Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join us for her online class, Managing the Present in Memoir, on April 16.

While walking home on the last day of first grade, I stared at the manila envelope containing my report card and thought, My god, that was the longest year of my life!

I loved school, but the days leading up to summer break inched by so slowly I felt the minutes—and even the seconds—pass by. As I trudged home, it seemed like I’d never make it to third grade, let alone middle school. And high school? Forget about it.

Now, at 51, I blink and weeks pass, leaving me to wonder where my time has gone.

Time is something I meditate on as a writer and writing coach. In storytelling, writers construct the illusion of time for the reader’s benefit. When managed well, it immerses readers in our narratives so deeply they lose track of time and live according to the world we’ve created—if only for a few minutes or hours.

Navigating time in your memoir can be tricky because there’s so much you could include. Yet you must balance your story’s forward momentum so major events neither fly by nor creep along so slowly that readers’ inner first graders wonder if they’ll ever make it to the last page.

Two common areas where memoirs bog down include the beginning and the middle.

For your memoir beginning, start as close to the main action—or perhaps a better phrase is main attraction—as possible. Accomplishing this feat requires you to determine what the main attraction actually is.

- For example, the main attraction in Kelly McMasters’ The Leaving Season is her relationship with her husband, R.

- In Tia Levings’ memoir A Well-Trained Wife, it’s her imprisonment inside an abusive fundamentalist marriage.

- For Margaret Lee’s Starry Field, the main attraction is her trips to Korea, where she interviewed her grandmother in hopes of learning the truth about her grandfather who’d been labeled a war criminal.

Identifying your memoir’s main attraction can help you avoid a sluggish start. But that won’t save you from the second, and most common, trap stories can fall into: the sagging middle.

How to maintain your memoir’s momentum

A story’s middle sags when the forward momentum stalls. This can happen when we encounter a series of seemingly unrelated events that fall into an “and then this happened, and then this happened” pattern, leaving us scratching our heads about how it all fits together.

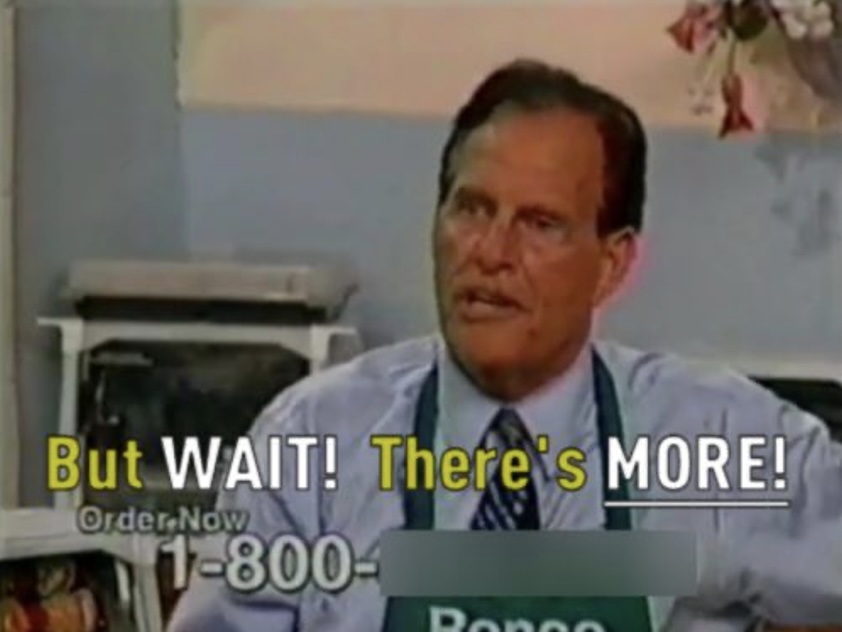

But even when events are interlinked, if writers cram too much into the main attraction, readers can feel like they’ve bought tickets not to a Cirque de Soleil performance that captivates and delights the senses, but to a Ron Popeil infomercial extravaganza. Just when you think things are wrapping up, he yells out, “But wait—there’s more!”

The antidote: learning to pace your memoir well. Pacing is how fast or slow something is delivered in your story, an element somewhat governed by word count. The more words you use, the more real estate something takes up. More real estate equals more importance for your reader.

What you include in that real estate also matters. Short action sequences, dialogue, and writing with ample white space are easier on the eye, leading to a faster read, whereas long, reflective, expository paragraphs take more time to digest. When we encounter page after page of long, detailed paragraphs or expansive scenes with little payoff, readers trudge rather than trot through your story. Ruthlessly cutting repetitive scenes and interesting-but-unrelated material is an important strategy to consider.

The art of compression

This is your powerful secret weapon. Many writers resist condensing their content, especially in memoir. They fear the true essence of their work will be lost if details are cut, which could hinder the reader’s appreciation of the enormity of an event or lead to misunderstandings.

But as RK Taylor shares in An Exercise in Compression, “Compression is the art of creating a full experience in a limited space.” Like distilling liquor, the process can lead to scenes that are sharper, bolder, and purer.

So how do we create these fine drinks of narrative?

First, identify the importance of each event in your memoir. Start with the moments that take up the most real estate. Decide whether they’re turning points or bridges between key events.

- In a turning point, the narrator makes a pivotal decision that impacts their biggest problem or helps them reach their goal.

- Bridge material generally contains little to no conflict but is essential for understanding your story’s plot. This could include scenes introducing a new character, the arrival of a character, or a plot point, like a scene where someone gives you something that plays a role later in the book.

When considering your book’s content, be wary of the very human urge to identify too many moments as turning points. When everything is fully developed into expansive scenes, it’s hard to identify what’s really important. I often liken it to being on an airport tarmac at peak flying time. So many engines are revving that you can’t hear the person trying to warn you about a plane in your path.

If, when referring to certain events, you say things like, “You need to know this to understand” or “For the story to make sense” you’re likely discussing bridge material that can be shortened. You can speed things up by summarizing what happened or skipping unnecessary steps.

Here’s an example of deftly handled bridge material from The Leaving Season that takes place in the wake of Kelly’s new husband R.’s heart attack. It reveals the arc of his recovery over a series of months:

As soon as R.’s leg was healed and the stress test revealed that his stent had worked, we packed our trunk with pails of white paint and headed back. In the fresh air and sun, R.’s color improved, the gray pallor giving way to a healthy pink. Friends came to visit, making long weekends out of their trips, helping to tear out the living room and reveal a latticework of strong, beautiful beams and old cut nails. R. worked slowly at first, testing his limits and letting others take over when he needed to rest. He still had chest pains every so often, but the doctor assured him that they were probably just muscle spasms, and every day he was able to work fifteen minutes longer than the day before.

Once you’ve separated the bridges from the turning points, identify the crux of each moment and how it serves your story. This will help you decide which details are crucial and whether you need a fully developed scene (a long scene) or if something shorter will suffice.

Don’t let the stakes of a scene fool you. In Amy Lin’s memoir Here After, her husband Kurtis’s sudden death unfolds over four short paragraphs. While terrible, that moment is a bridge between her life with him and her life without him, which begins with a multi-page description of the hours when she sits with his body and then says goodbye.

Once you’ve identified your event’s key details, capitalize on them and eliminate the rest. The final step to compressing material is writing with precision. First, address low-hanging fruit by nixing passive voice, adverbs, and filler words like just and that. Next, replace phrases with more precise words, such as remove instead of get rid of. Eliminate more by experimenting with sentence structure. If you find cutting words a challenge, turn it into a game by limiting your word count. You’ll be surprised by the opportunities you’ll find when you apply this constraint to your material.

Does this kind of revision take time?

Yes.

Is it worth the effort?

Absolutely.

Compressing minor scenes and summarizing bridge material can maximize the power of your story by creating a rhythm for your narrative that, like a heartbeat, carries readers through every twist and turn. If paced exceptionally well, they’ll not only lose track of time; their inner first graders will be grateful for having lived through it alongside you.

If you enjoyed this article, join us for Lisa’s online class Managing the Present in Memoir on April 16.

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)

![How Marketers Are Using AI for Writing [Survey]](https://www.growandconvert.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ai-for-writing-1024x682.jpg)

![Ecommerce Customer Journey Mapping — How to Set Potential Shoppers Up to Buy [Tips & Template]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/ecommerce-Sep-13-2023-09-08-01-7144-PM.png)