REBEL ANGEL

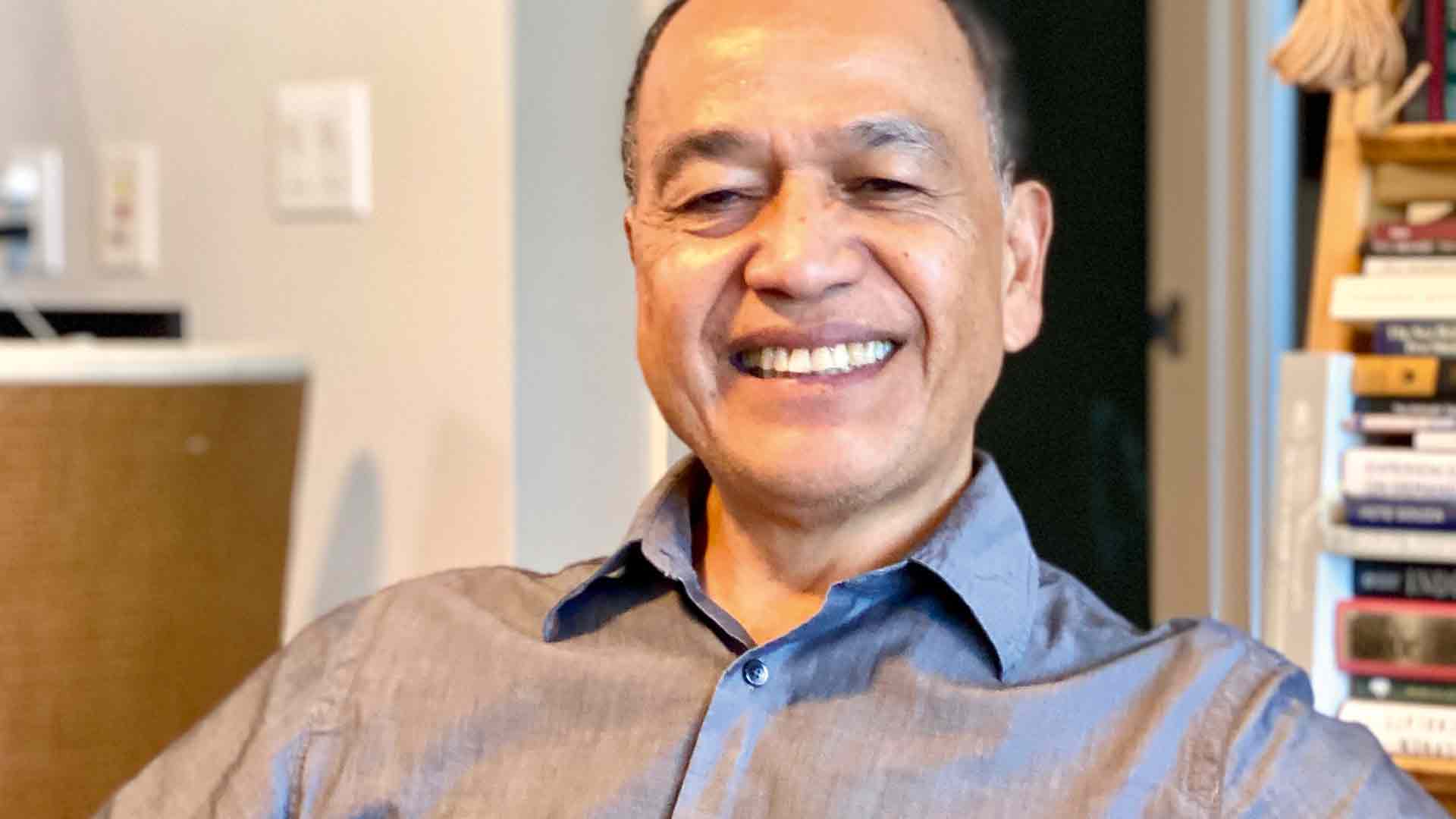

Irish poet and novelist Rooney creates a well-researched account of the eventful, peripatetic life of journalist, photographer, and fiction writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908-42). The strong-willed, glamorous daughter of a wealthy Swiss silk-manufacturing family, Schwarzenbach grew from a young tomboy into a daring, ambitious, yet troubled woman. To Thomas Mann, the restless Annemarie seemed a “rebel angel.” In a family that supported the Nazis, she was violently opposed. Her controlling mother, who had a 30-year relationship with a prominent female opera singer, could not countenance Annemarie’s lesbian liaisons. Distancing herself from her mother, Rooney asserts, became her life’s work. Rooney chronicles Schwarzenbach’s love affairs; her marriage of convenience to a French diplomat, which afforded her a coveted diplomatic passport; and her friendships, the most enduring of which was with Mann’s children Klaus and Erika. Klaus, a frequent travel companion, introduced her to the gay underworld of Berlin, rife with drugs. By 1932, she was a morphine addict. Psychologically fragile, she was in and out of psychiatric clinics, attempted suicide, and taxed the patience of friends with her overwhelming neediness, as she spiraled deeper into addiction and alcoholism. Writing and traveling, Rooney asserts, served her as “lodestones in time of crisis”: reporting, photojournalism, and even archaeological digs took her through Europe—Paris, Venice, Zurich, Nice—and the Middle East, Persia, Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, and the Balkans; she traveled to the U.S. three times. During her last trip there, in 1940, she met the newly hailed young novelist Carson McCullers, who became besotted with her, an attraction that was not reciprocated. Despite her mother’s burning her letters and diaries, Rooney mines ample German, French, and English sources to inform a thorough biography.

Irish poet and novelist Rooney creates a well-researched account of the eventful, peripatetic life of journalist, photographer, and fiction writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908-42). The strong-willed, glamorous daughter of a wealthy Swiss silk-manufacturing family, Schwarzenbach grew from a young tomboy into a daring, ambitious, yet troubled woman. To Thomas Mann, the restless Annemarie seemed a “rebel angel.” In a family that supported the Nazis, she was violently opposed. Her controlling mother, who had a 30-year relationship with a prominent female opera singer, could not countenance Annemarie’s lesbian liaisons. Distancing herself from her mother, Rooney asserts, became her life’s work. Rooney chronicles Schwarzenbach’s love affairs; her marriage of convenience to a French diplomat, which afforded her a coveted diplomatic passport; and her friendships, the most enduring of which was with Mann’s children Klaus and Erika. Klaus, a frequent travel companion, introduced her to the gay underworld of Berlin, rife with drugs. By 1932, she was a morphine addict. Psychologically fragile, she was in and out of psychiatric clinics, attempted suicide, and taxed the patience of friends with her overwhelming neediness, as she spiraled deeper into addiction and alcoholism. Writing and traveling, Rooney asserts, served her as “lodestones in time of crisis”: reporting, photojournalism, and even archaeological digs took her through Europe—Paris, Venice, Zurich, Nice—and the Middle East, Persia, Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, and the Balkans; she traveled to the U.S. three times. During her last trip there, in 1940, she met the newly hailed young novelist Carson McCullers, who became besotted with her, an attraction that was not reciprocated. Despite her mother’s burning her letters and diaries, Rooney mines ample German, French, and English sources to inform a thorough biography.

.jpg)

![How to Find Low-Competition Keywords with Semrush [Super Easy]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/73/62/7362f16fb9e460b6d58ccc09b4a048b6/how-to-find-low-competition-keywords-sm.png)

![How Marketers Are Using AI for Writing [Survey]](https://www.growandconvert.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ai-for-writing-1024x682.jpg)

![Beyond ROAS: Aligning Google Ads With Your True Business Objectives [Webinar] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/featured-1-808.png)