Don’t Ruin the Mystery: How to Reflect in Memoir Without Giving It All Away

What draws readers into your story is the mystery of how you achieved your transformation, so reflection must be handled carefully.

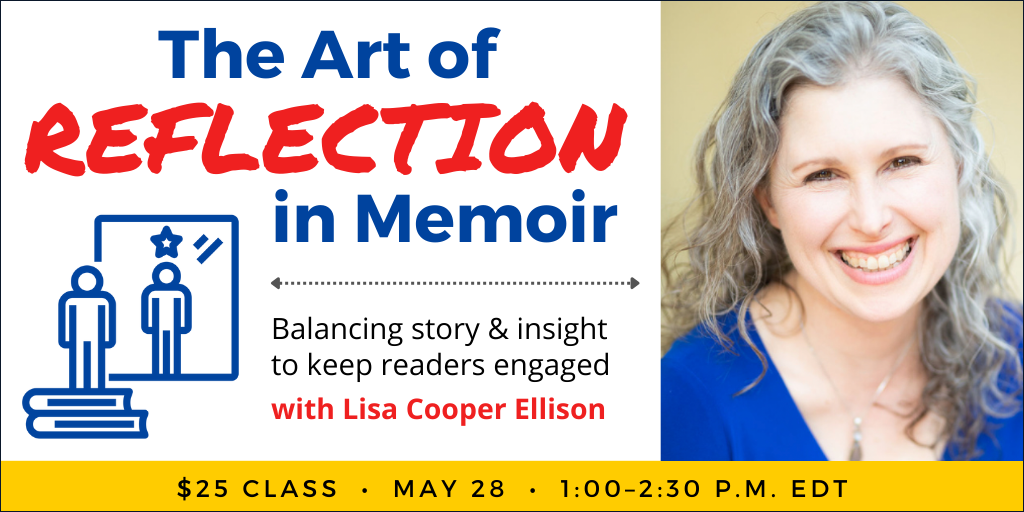

Today’s post is by writer and editor Lisa Cooper Ellison. Join her on Wednesday, May 28, for the online class The Art of Reflection in Memoir.

Memoirists often ask, “How do I incorporate my reflections on events into my memoir?”

Here’s the unsatisfying answer: it depends.

Before we explore why it depends, let’s unpack what writers mean when they ask this question. In its purest form, reflection is a form of exposition, or telling, that conveys the writer’s understanding of past events. In Acetylene Torch Songs: Writing True Stories to Ignite the Soul, Sue William Silverman uses the Aware and Unaware voices to explain this concept.

- The Unaware Voice represents the person experiencing the events—living them without understanding their meaning.

- The Aware Voice, on the other hand, is the one we use as writers to inject insight into our stories, offering a deeper perspective on the events we recount.

Elevating reflection in our memoir—everything from simple “here’s what this means” or “later I learned” statements—requires you to integrate the Aware Voice into your narrative without disrupting its flow or lecturing readers about how they should feel. The balance is crucial for transforming your memoir into a compelling, introspective work of art.

The balance of reflection in your memoir

The amount of reflection you’ll find in a memoir can depend on your subgenre. For instance:

- Memoirs in essays, like The Leaving Season by Kelly McMasters, Abandon Me by Melissa Febos, or Eiren Caffall’s The Mourner’s Bestiary, tend to have more explicit reflection.

- Straightforward novel-like narratives, such as Allison Landa’s Bearded Lady, The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney, and Townie by Andre Dubus III, often feature less direct reflection and focus more on storytelling.

You should also consider your personal writing style. Writers like Leslie Jamison, Meghan Daum, and Jennifer Niesslein are masters of voice-driven reflections that captivate as they brilliantly connect ideas, while others, like Jeannette Walls, Laura Cathcart Robbins, and Sarah Perry, let their vivid scene writing sparkle.

The danger of over-indulging in early reflections

The challenge is not just how much reflection to include, but in how—and when—you reflect. During a memoir class in 2014, Sharon Harrigan quoted her mentor Debra Gwartney as saying, “The subtitle of every memoir is how I coped.”

I would add that the meta of every memoir is that you survived well enough to write a book about it. In other words, your entire book is a reflection on what happened and its significance.

What draws readers into your story is the mystery of how you achieved your transformation or how you answer the question your opening poses. For example, in Rose Andersen’s memoir, The Heart and Other Monsters, the primary question is, “Did my sister overdose or was she murdered?” It’s followed closely by the question haunting Rose: “As my sister’s keeper, should I have prevented it?”

The more your early reflections hint at how everything is OK now or spell out the main lessons for the reader, the less mystery there is to solve, and, as a result, the less reason to read your book.

Instead, adopt this as your north star: use your book to share your experience, strength, and hope. As you do so, trust your intelligent readers to fill in the blanks and determine which lessons and strategies best fit their circumstances.

3 steps for inserting reflection in your memoir

1. Start off the page. Early memoir drafts often include a series of reported events or reflections on them. To balance the role of the Aware and Unaware Voices in your manuscript, try this exercise:

- Choose a chapter or scene to focus on.

- In your journal, identify which voice dominates.

- If the Aware Voice is more prevalent, can you craft scenes that show what happened?

- If all you see is the Unaware Voice, free-write about what you now know and the lessons you learned. If that feels difficult, start with why you wanted to write this scene. What do you hope to convey to readers?

2. Deepen your understanding. Memoir is a journey of discovery. Even if you think you’ve grasped the meaning of your experiences, approach them with fresh curiosity. Research and fact-check your scenes, write from other perspectives, and look for connections that might deepen your understanding of what happened. Note what you’ve discovered, and as you do so, identify each scene’s true purpose in your book.

3. Vary your reflection strategies. Once you know where to insert your reflections, there are a few ways to infuse your wisdom into your story.

You can directly insert the retrospective voice into your narrative, something Laura Cathcart Robbins does in the first chapter of her memoir Stash: My Life in Hiding to heighten her story’s central conflict.

When people talk about enduring, it’s usually in an admirable way. They bravely endure the pain of childbirth, or they endure poverty or hunger. The goal is to make it through these things and come out “stronger,” right? I’ve seen people endure unhappy marriages for years, justifying their cowardice by saying things like, “it’s too complicated,” or “it’s better than being alone.” I’ve been blaming the demise of my marriage on my addiction, which blew up spectacularly this year. But if I’m being honest, we’ve been unhappy for longer than that. It feels as though I’ve been hanging onto a window ledge for the past two years and now my fingers are starting to slip. All this time I’ve been so terrified of the fall that I haven’t even dared think about where I might land. But what if I’m afraid of the wrong thing? What if it’s not where I land that should concern me, but why I’m still hanging on?

You can also look for events after your story ends that add layers of meaning to passages in your book. Notice how Tobias Wolff uses a flash forward from his military service to make sense of his actions in his memoir, This Boy’s Life.

Why were Jack and his brothers digging post holes? A fence there would run parallel to one that already enclosed the farmyard. The Welches had no animals to keep in or out—a fence there could serve no purpose. Their work was pointless. Years later, while I was waiting for a boat to take me across a river, I watched two Vietnamese women methodically hitting a discarded truck tire with sticks. They did it for a good long while and were still doing it when I crossed the river. They were part of the dream from which I recognized the Welches, my defeat dream, my damnation dream, with its solemn choreography of earnest useless acts.

Finally—and this is where reflection truly becomes art—you can insert reflective thoughts within scenes, like Allison Landa does in her memoir, Bearded Lady.

Nails looks different than the last time I saw her. That was years ago, and now the youthful freshness has faded from her face. In their place, lines have set in, deep creases that each seem to showcase a sad story. Her hair is the same color as the woman who glared at me at Gaylords. She is missing a tooth, and the rest seems jagged. Is this all new, or had I just never noticed?

The bolded line in the above passage is an example of interiority, or the narrator’s direct thoughts when an event occurs. While it’s possible Allison had that exact thought while she was looking at her mother, inserting it at the end of this paragraph signals that Allison’s feelings about her mother have softened. Interiority is just one of the story elements you can play with to subtly incorporate your insights into your memoir and make revision more fun.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, May 28, for the online class The Art of Reflection in Memoir.

![Brand and SEO Sitting on a Tree: K-I-S-S-I-N-G [Mozcon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_LidiaInfante_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1749465874&s=56275e60eb1f4363767c42d318c4ef4a#)

![How To Launch, Grow, and Scale a Community That Supports Your Brand [MozCon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_Areej-abuali_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1747732165&s=beb7825c980a8c74f9a756ec91c8d68b#)

![Clicks Don’t Pay the Bills: Use This Audit Framework To Prove Content Revenue [Mozcon 2025 Speaker Series]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/Mozcon2025_SpeakerBlogHeader_1180x400_Hellen_London.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1747758249&s=9f3c5b1b7421f862beace1cb513053bb#)

![The 11 Best Landing Page Builder Software Tools [2025]](https://www.growthmarketingpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/best-landing-page-software-hero-image-1024x618.png?#)

![Is Google About To Bury Your Website? [Webinar] via @sejournal, @lorenbaker](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/3-271.png)

![Marketers Using AI Publish 42% More Content [+ New Research Report]](https://ahrefs.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/marketers-using-ai-publish-42-more-by-ryan-law-data-studies-1.jpg)

![Social media image sizes for all networks [June 2025]](https://blog.hootsuite.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Social-Media-Image-Sizes-2023.png)

![The HubSpot Blog’s AI Trends for Marketers Report [key findings from 1,000+ marketing pros]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/state-of-AI-1-20240626-53394.webp)

![AI can boost conversions from your web page — HubSpot’s CMO shows you how [tutorial]](https://knowledge.hubspot.com/hubfs/ai-1-20250605-395473.webp)

![The state of inclusive marketing in 2025 [new data + expert insight]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/inclusive-marketing-report.webp)