THE FRIENDSHIP BENCH

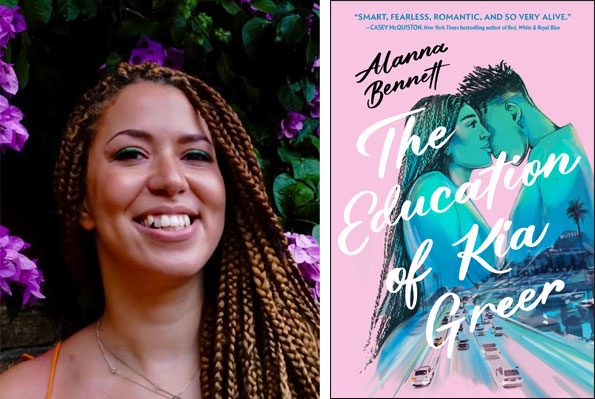

When the author began the Friendship Bench project with 14 grandmothers in the early 2000s, there were only six practicing psychiatrists in Zimbabwe. (Today, the number remains less than 20.) Designed to address the limited access many Zimbabweans have to mental health professionals, the Friendship Bench project deploys a team of “lay psychotherapists” to provide a listening ear, sage wisdom, and guidance to those in need. The project also helps to break down cultural stigmas associated with mental health; Chibanda came to realize that wooden park benches located under trees and occupied by welcoming grandmothers provided a welcome “safe space” and alternative to the “crowded clinic” where specialists like himself only had a few minutes with each patient. Featuring the stories of individuals whom Friendship Benches have helped, the book highlights women like Farai, an HIV-positive mother riddled with self-doubt and shame whose life was turned around after just one conversation with a compassionate grandmother on a bench. While the author, a trained medical doctor and professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, is well versed in modern pharmacology, he highlights the power of indigenous African approaches to mental health and explicates concepts like the Shona notion of kufungisisa(“thinking too much”). Chibanda also tells the fascinating story of the Friendship Bench project’s growth, which exploded following a TED Talk delivered by the author that received millions of views. The project is now a “full-fledged NGO” with an administrative and training center; toolkits are offered to readers who want to “Join the Movement” and start Friendship Bench projects in their own communities. Chibanda’s writing style is empathetic and deeply personal—his text is accessible to readers both inside and outside of the psychiatric profession, and it’s accompanied by a wealth of photographs.

When the author began the Friendship Bench project with 14 grandmothers in the early 2000s, there were only six practicing psychiatrists in Zimbabwe. (Today, the number remains less than 20.) Designed to address the limited access many Zimbabweans have to mental health professionals, the Friendship Bench project deploys a team of “lay psychotherapists” to provide a listening ear, sage wisdom, and guidance to those in need. The project also helps to break down cultural stigmas associated with mental health; Chibanda came to realize that wooden park benches located under trees and occupied by welcoming grandmothers provided a welcome “safe space” and alternative to the “crowded clinic” where specialists like himself only had a few minutes with each patient. Featuring the stories of individuals whom Friendship Benches have helped, the book highlights women like Farai, an HIV-positive mother riddled with self-doubt and shame whose life was turned around after just one conversation with a compassionate grandmother on a bench. While the author, a trained medical doctor and professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, is well versed in modern pharmacology, he highlights the power of indigenous African approaches to mental health and explicates concepts like the Shona notion of kufungisisa(“thinking too much”). Chibanda also tells the fascinating story of the Friendship Bench project’s growth, which exploded following a TED Talk delivered by the author that received millions of views. The project is now a “full-fledged NGO” with an administrative and training center; toolkits are offered to readers who want to “Join the Movement” and start Friendship Bench projects in their own communities. Chibanda’s writing style is empathetic and deeply personal—his text is accessible to readers both inside and outside of the psychiatric profession, and it’s accompanied by a wealth of photographs.

![The 11 Best Landing Page Builder Software Tools [2025]](https://www.growthmarketingpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/best-landing-page-software-hero-image-1024x618.png?#)

![What Is Generative Engine Optimization [Tips & Workflows To Do It]](https://moz.com/images/blog/banners/What-Is-Generative-Engine-Optimization-Tips-Workflows-To-Do-It-1.png?auto=compress,format&fit=crop&dm=1745607929&s=6f75f1f02c531af0f80acb12517c8bab#)

![Cracking the SEO Code: Regain Control of Search Visibility in the Age of AI [Webinar] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/featured-73.png)