CLASS MATTERS

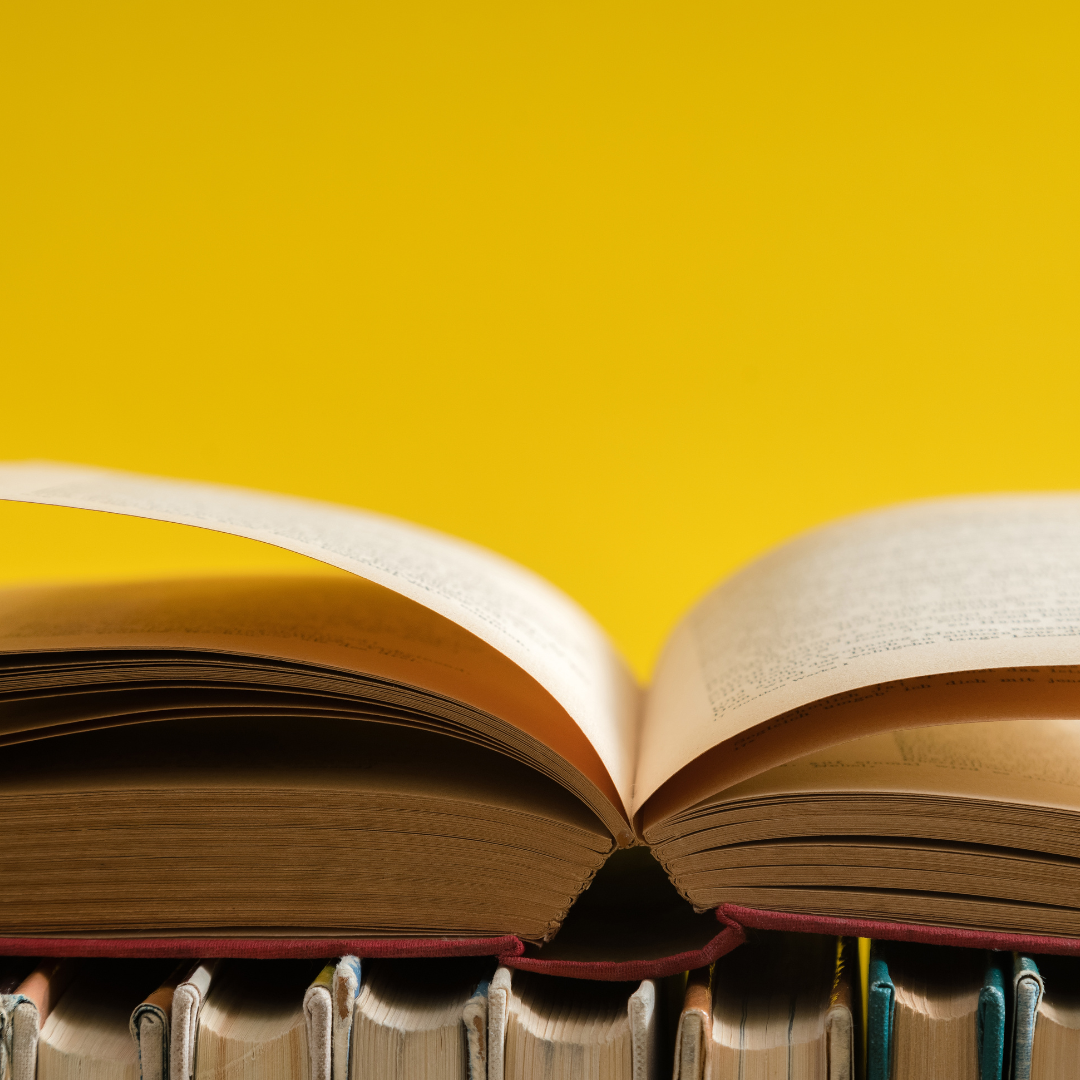

Kahlenberg is well known—and a source of controversy—for having aligned, though a liberal, with conservative thinkers in arguing against the affirmative action of old. The goals of racially based affirmative action are, he writes, “valid”: “It is crucial that in a multicultural democracy, students learn to appreciate and value individuals of all backgrounds.” Yet, as constructed until recently, race-based affirmative action standards at state as well as private schools favored moneyed applicants, as well as legacy admissions. This may yield diversity of a kind, but it deprecates the efforts of economically disadvantaged students of whatever race. With a Duke economist, Kahlenberg gamed the results of class-based admissions at Harvard and the University of North Carolina (where, perhaps surprisingly, there are 16 times more students from wealthy than from poor backgrounds), and the two discovered that the outcomes would be more equitable than race-based admissions: “We found that universities could produce both racial and economic diversity and maintain high academic standards if they invested in this new approach.” The keyword there is “invested,” because with likely fewer legacy and donor funds, it would cost schools more to offer financial aid to the economically disadvantaged than to do things as usual. However, things as usual are changing, anyway: The Supreme Court has ruled against race-based admissions, which, Kahlenberg cogently argues, may usher in a “fairer form of affirmative action.” He adds that this may also benefit progressives, who have been losing ground steadily among the electorate precisely because most Americans simply dislike race-based regulation. He also notes, in passing, that the “academic achievement gap,” measured among other things by SAT scores, is twice as large when gauged by class as by race.

Kahlenberg is well known—and a source of controversy—for having aligned, though a liberal, with conservative thinkers in arguing against the affirmative action of old. The goals of racially based affirmative action are, he writes, “valid”: “It is crucial that in a multicultural democracy, students learn to appreciate and value individuals of all backgrounds.” Yet, as constructed until recently, race-based affirmative action standards at state as well as private schools favored moneyed applicants, as well as legacy admissions. This may yield diversity of a kind, but it deprecates the efforts of economically disadvantaged students of whatever race. With a Duke economist, Kahlenberg gamed the results of class-based admissions at Harvard and the University of North Carolina (where, perhaps surprisingly, there are 16 times more students from wealthy than from poor backgrounds), and the two discovered that the outcomes would be more equitable than race-based admissions: “We found that universities could produce both racial and economic diversity and maintain high academic standards if they invested in this new approach.” The keyword there is “invested,” because with likely fewer legacy and donor funds, it would cost schools more to offer financial aid to the economically disadvantaged than to do things as usual. However, things as usual are changing, anyway: The Supreme Court has ruled against race-based admissions, which, Kahlenberg cogently argues, may usher in a “fairer form of affirmative action.” He adds that this may also benefit progressives, who have been losing ground steadily among the electorate precisely because most Americans simply dislike race-based regulation. He also notes, in passing, that the “academic achievement gap,” measured among other things by SAT scores, is twice as large when gauged by class as by race.

![How Marketers Are Using AI for Writing [Survey]](https://www.growandconvert.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ai-for-writing-1024x682.jpg)

![311 Instagram caption ideas [plus free caption generator]](https://blog.hootsuite.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/instagram-captions-drive-engagement.png)

![How to Create a Complete Marketing Strategy [Data + Expert Tips]](https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/marketing-strategy.webp)